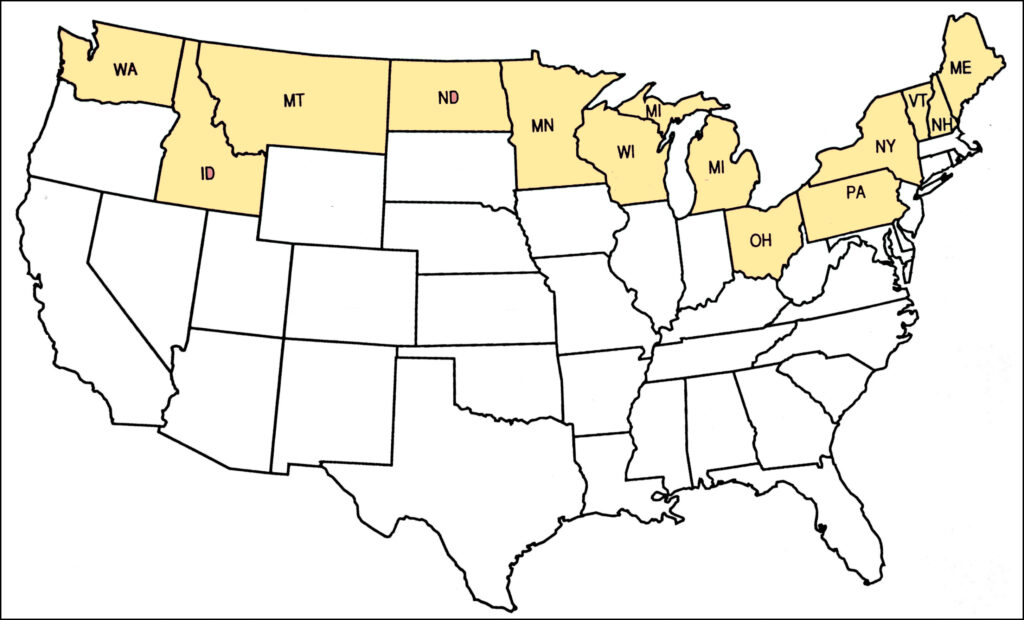

The CCIPR is asking for legislation to regulate invasive plants. We know people may be concerned that these changes will reduce options for gardeners or that the compliance costs may impact the horticultural industry. However, we believe the benefits of safeguarding the health of our economy, ecosystems and the public outweigh the potential negative impacts. We are not alone. All the states along Canada’s southern border prohibit the sale of certain invasive plants.

Let’s look at your potential concerns.

“Do regulations work? Are there examples?”

Yes! Every state along Canada’s southern border regulates plants in the horticultural trade in some way.

Many American states have begun regulating invasive ornamental plants, because the costs of doing nothing are simply too high. Let’s just look at the 13 states along Canada’s southern border. This is just a quick summary, but click the links to read more about regulated plants.

- Idaho ID – has prohibited groups of plants called brooms (Cytisus, Chameacytisus, Genista, Spartium) and many other ornamentals plants like yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus) (Idaho Regulated Plants).

- Maine ME – regulates 33 plants that are “a direct threat to what we value … Species like Japanese barberry and multiflora rose can form thorny, impenetrable thickets in forests and agricultural fields. Aquatic invasives can choke waterways, making it difficult to boat or swim,” (Maine Regulated Plants).

- Michigan MI – prohibits terrestrial species like Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and also regulates 18 aquatic plants like Purple loosestrife, (Michigan Regulated Plants).

- Minnesota MN – prohibits the sale of 45 plants like Amur maple (Acer grinnala), Norway maple (Acer platanoides) and all cultivars. Some species are allowed for sale with restrictions … (Minnesota terrestrial invasive plants).

- Montana MO – bans the sale of ornamental plants like Scotch broom, (Cytisus scoparius), Yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus), Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) and Parrot’s feather watermilfoil (Myriophyllum aquaticum and M. brasiliense), (Montana Noxious Weeds).

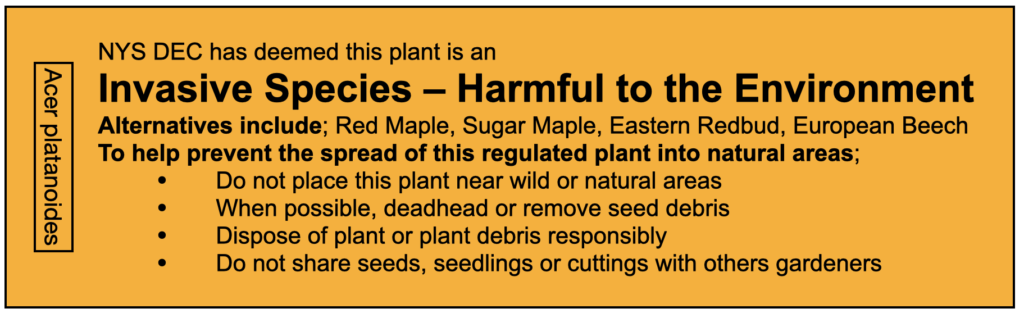

New Hampshire NH – prohibits 35 species such as Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and others that are highly competitive and dominant in many of New Hampshire’s natural and artificial landscapes. - New York NY – prohibits over 70 species (NY Prohibited List), but has chosen to regulate some additional plants in the horticultural trade with labelling regulations. So Norway Maple (Acer platanoides) may be sold, but the plant must be sold with a label.

- North Dakota ND – prohibits a dozen noxious weeds including: Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria and L. virgatum with all cultivars) and Saltcedar (Tamarisk spp.), (North Dakota list).

- Ohio OH – “In order to protect native plant species and thwart the growth of invasive plant species, 38 plants have been declared invasive in Ohio. No person shall sell, offer for sale, propagate, distribute, import or intentionally cause the dissemination of any invasive plant in the state of Ohio. Currently, callery pear (Pyrus calleryana) can be sold until January 2023,” (Ohio Plant List).

- Pennsylvania PE – regulates Noxious Weeds including some ornamental plants found to be injurious to public health, crops, livestock, agricultural land or other property. These cannot be sold, transported, planted, or otherwise propagated in Pennsylvania. They include Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), (Penn Noxious Plant List).

- Vermont VT – prohibits the sale of 40 plants that can out compete and displace plants in natural ecosystems and managed lands; and can have significant environmental, agricultural and economic impacts. The list includes goutweed/bishopsweed (Aegopodium podagraria), tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), flowering rush (Butomus umbellatus), bush honeysuckles (Lonicera x bella, L. japonica, L. maackii, L. morrowii, L. tatarica), burning bush (Euonymus alatus), yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus), Amur maple (Acer ginnala), (Vermont Noxious Weeds).

- Washington WA – has one of the most extensive lists of regulated plants. “Every year noxious weeds and other invasive exotic plants cost Washington millions of dollars in lost production, public and private control costs, and environmental degradation. These exotic introductions to Washington have displaced native plant communities, damaged range and recreational lands, and degraded fragile wetlands. Escaped ornamentals are one significant source of infestation. It is often difficult to predict which ornamentals will be invasive and aggressive. Scotch broom, purple loosestrife, and kochia are prime examples of plants which have escaped cultivation and caused enormous economic and environmental damage. …These regulations will serve to present the continued introduction of the problem plants into Washington,” (Washington Regulated Plants and Seeds).

- Wisconsin – prohibits 41 species including Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda) and Chinese wisteria (Wisteria sinensis), (Wisconsin list).

While this regional approach to regulating invasive plants is a step forward, the approaches are inconsistent from state to state and there is no strategic federal framework. We can improve upon this in Canada. We need an improved nationally coordinated, multi-jurisdictional response to invasive plants. For instance:

- Most of Canada’s Legislation was written before the Invasive Alien Species issue was widely understood.

- Most Acts, both nationally and provincially, deal with pests, substances or organisms and are stretched to address invasive plants.

- Many of the Acts used to prohibit invasive plants were written to deal with specific issues as they relate to agriculture or forestry (i.e. Plant Protection Acts), and only prohibit plants not yet established in Canada.

- It is unclear which department is responsible for aquatic invasive plants.

- There is no central department or agency that oversees all preventative invasive species or biosecurity efforts in Canada, across all invasion pathways. For instance, it is unclear which department is responsible for aquatic invasive plants. (Newfoundland: Legislative Review; Reid, 2021)

We can fix this. Canada needs to harmonise policies and standards for prevention, detection and management of invasive plants. This should include legislation to limit the spread of both terrestrial and aquatic invasive plants through the horticultural and aquarium/pet trades.

“They are not a problem in my yard … I can control them”

Some plants may be manageable, but plant labels are needed to inform buyers of the risks, so they can be responsibly controlled.

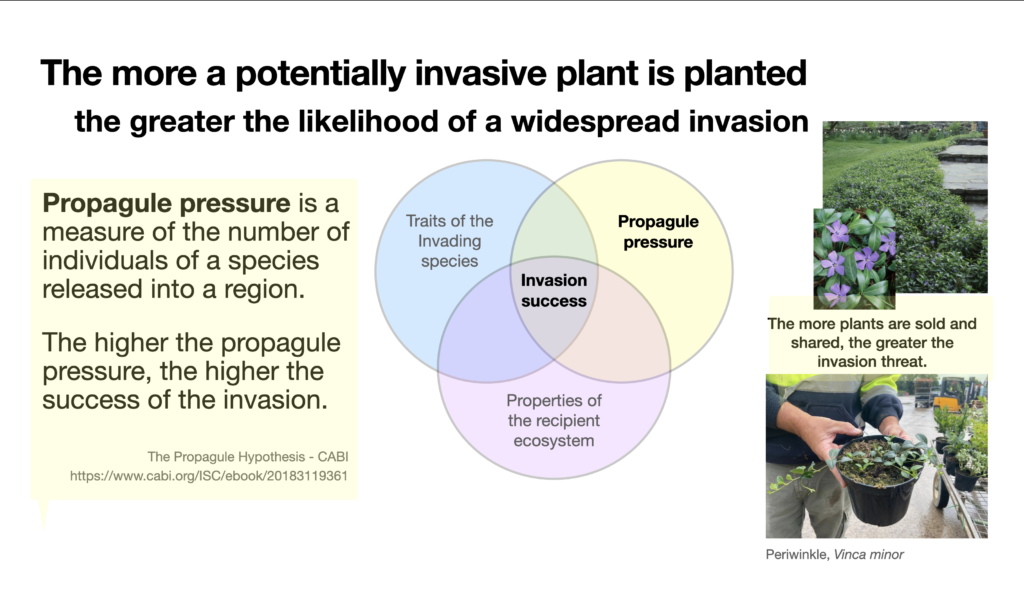

Gardeners are often unaware that wind or birds or animals can spread seeds and fruits of invasive plants to neighbouring gardens and natural lands. New York requires labels to inform the gardeners of the potential risks. Armed with information, gardeners may be able to prevent the local spread of an invasive plant by confining it, removing seed heads and weeding out unwanted escaped growth. But we need to remember that gardens change hands, so plants sold with warning labels should be minimally invasive species like catnip (Nepeta cataria) and not “transformers” like periwinkle (Vinca minor), which can invade and dominate sites indefinitely.

“Regulation will hurt the nursery industry”

There will be costs associated with transitioning to non-invasive stock, but gardeners will continue to want plants and there are opportunities for a Greener Industry.

The industry itself has recognized the need for change. The Canadian Society of Landscape Architects (CSLA) and the Canadian Nursery Landscape Association (CNLA) were part of a working group that developed a NATIONAL VOLUNTARY CODE OF CONDUCT FOR THE ORNAMENTAL HORTICULTURE INDUSTRY. The Code calls for the phase-out and disposal of existing stocks of high-risk invasive species or cultivars and asks growers to select only non-invasive ornamentals (Code of Conduct).

This Code has not been widely adopted. To help the industry move forward, a national database is needed to provide risk analyses in a centralized system that all provinces and territories could use. This would ensure that jurisdictions with fewer resources would be able to address the invasive species problem. A national framework for regulations is needed along with restrictions clearly identifying which species are of the greatest concern and how they can be regionally managed.

Canadian consumers will regain confidence and know that the plants they buy are not harmful to their nation. The gardening public will continue to purchase plants. There will be new opportunities to grow regionally appropriate plant species. Provinces like Quebec are enhancing local economic development by labelling regional products with ‘appellation réservée’–such labels could be used to recognize the importance of a plant to the region. Innovative nursery growers may capitalize on regional botanical uniqueness. Importers and breeders can focus on plants that support ecosystem health. This process can be transformative for the industry and in the end benefit all Canadians and global biodiversity.

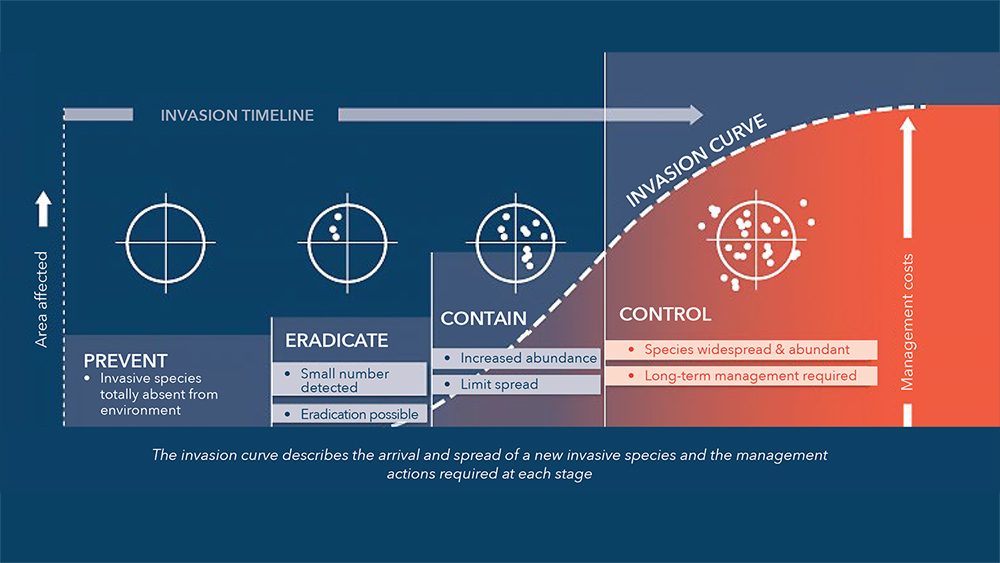

“Invasive species are everywhere. It is too late to control them.”

There are many positive examples of successful restoration work. We need to support these efforts that benefit us all.

Invasive plants can negatively impact our health, water quality, food costs, and our ability to enjoy nature. If we do nothing to slow the spread of invasive species, costs and impacts will continue to grow dramatically. We can’t afford to lose more natural lands and the services they provide us.

For this reason, many municipalities and NGOs are working to remove invasive plants and restore the health of forests, wetlands and prairies. From Nanaimo in B.C. to the Limestone Barrens of Newfoundland, money is invested and public employees, volunteers, farmers and foresters work to remove invasive plants from their regions to protect endangered species, to improve crop production, to improve hunting and fishing, reduce fire risk, protect water resources and reduce disease risks. Continued circulation of invasive plants, increases the risks of those plants finding their way back to restored sites and invading new sites.

“This would limit our choices.”

Only a small fraction of introduced plant species are highly invasive and require regulation.

Our herbaceous peonies and apple trees are not the problem. There are over 5000 plant species in Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency lists only 1.4% of introduced ornamental plants as problematic, (Invasive Alien Plants in Canada – Technical Report, 2008). A recent study conducted by the seven public gardens across North America concurred. Only a small percent of plants in the Botanical Gardens and Arboretums were causing harm. “Garden A: 17,469 total taxa, of which 230 are problematic (1.3%),” (Culley, 2021).

That same study, showed that 89% of invasive woody plants, 65% of invasive vines and about 31% of invasive herbaceous plants were intentionally introduced as ornamentals. Curbing the spread of this limited group of plants would limit “propagule pressure” and stop further damage to our natural communities, commercial agriculture, forest crop production, and human health.